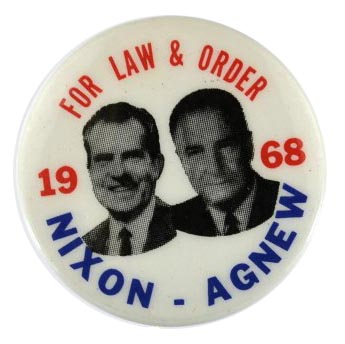

1968 "Law and Order" campaign ad for Richard Nixon that helped him win the White House.

Through the calculated use of seemingly innocuous buzz words or “dog whistles![]() - ambiguous messaging used to stoke racial fear and anxiety and/or to covertly signal allegiance to certain subgroups of an audience.

- ambiguous messaging used to stoke racial fear and anxiety and/or to covertly signal allegiance to certain subgroups of an audience.

,” politicians can quietly stoke racial fears and anxiety that reside not-so-far beneath the surface of a target audience. And they can do so, without taking the political risk of openly appealing to racism, since the more nefarious implied messages can be disregarded as being completely unintentional, while still communicating them to the desired group.

This level of calculated obscurity was not in play in 1964, when Conservative Party members in the UK were campaigning with the slogan, “If you want a n***** for a neighbour, vote Labour.”[1] Although the Labour Party did win the 1964 election, the tactics were later described by the Prime Minister as “utterly squalid,” reflecting the changing times and a shift in public sentiment away from such overt forms of racism.

Using a similar strategy, in 1968, George Wallace ran on an openly pro-segregation platform in the U.S. But in this case, despite his popularity in Southern states, he was defeated in a landslide by Richard Nixon. Exercising more nuance, Nixon’s calls for “law and order” effectively played into the same fears of white suburbanites, about encroaching ethnic minority communities and recent civic changes, like court ordered busing, while also being palatable to the wider majority of voters.[2]

Taking a similar page from the “law and order” playbook, in a 1996 speech championing her husband’s crime legislation, Hillary Clinton painted a dehumanizing picture of marauding inner-city teens.[3] Describing the youth, she said, “They are often the kinds of kids that are called superpredators – no conscience, no empathy. We can talk about why they ended up that way, but first, we have to bring them to heel." And while nowhere in the speech did Clinton directly single out Black or Brown youth, it was a reasonable inference that she was doing just that.

That same ambiguity can be found in “Make America Great Again,” a slogan first used in Ronald Reagan’s successful 1980 presidential campaign (as "Let's make America great again") and brought back into service in 2016 by the Trump campaign. Like the best of dog whistles, the slogan can mean different things to different people. Does “again” refer to the 1950s, when the U.S. had emerged victoriously from World War II, or that same period, when Blacks were unable to vote and women didn’t work outside the home?[4] Does “again” refer to the booming U.S. economy of the late 90’s or an earlier time when middle-class, suburban neighborhoods were still largely white? While the slogan invites racist thinking, it leaves room for other, more benign, interpretations.

Beyond just stoking racial fears, dog whistles can also be used to send a sort of secret code to signal allegiance or gain credibility with specific subgroups. This can take the form of repeating phraseology that is commonly used in certain spaces, yet would go unrecognized by others. This type of membership signaling was used by George W. Bush in his 2003 State of the Union address, in his reference to “wonder-working power, in the goodness and idealism and faith of the American people.” This phrase, borrowed from the oft-sung hymn “Power in the Blood,” would have resonated with Evangelical Christians, while appearing to merely be colorful language to anyone else. [5]

And so the dog whistle carries on as a reliable instrument to gain votes from the further ends of the political spectrum, without alienating the wider majority of voters. The dog whistle provides politicians, past and present, a stealth frequency to signal allegiance and membership, or a safe way to deliver racist messaging, while granting them plausible deniability from having to own it.