In times of uncertainty or crisis, familiar tactics often resurface that simplify complex problems and provide the public with plausible explanations for their suffering. As political polarization deepens and trust in institutions continues to erode, prominent world leaders are increasingly turning to age-old strategies like scapegoating and demonization to exploit fear and division.[1]

By channeling societal frustrations toward a specific group or individual, leaders can create an "us versus them" dynamic, uniting supporters while isolating perceived enemies. Demonization intensifies this effect, portraying the targeted group as not just problematic but inherently dangerous, immoral, or unworthy of trust. This fosters a culture of fear and loyalty, where followers feel compelled to support the leader as a safeguard against the alleged threat.

History is replete with examples where past rulers have wielded scapegoating as a means of consolidating power and manipulating public sentiment. One of the most infamous cases is Stalin’s scapegoating of Leon Trotsky during the aftermath of the Russian Revolution. Stalin blamed Trotsky for a host of issues plaguing the post-revolution USSR, even though Trotsky had been exiled long before these problems arose. To divert attention from the terror and suffering caused by his own brutal leadership,[2] Stalin channeled generalized public fears into hatred for Trotsky, branding him as a capitalist stooge and counter-revolutionary to redirect blame away from his own administration. But while Stalin did create a scapegoat in Trotsky, he fell short of fully severing Trotsky’s connection to the common people.[3]

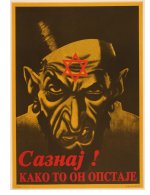

Anti-Jewish poster issued

Anti-Jewish poster issuedIn that regard, Hitler did not fall so short. He drew stark, unequivocal lines between the so-called Aryan people and groups he deemed inferior or dangerous, including Jews, Poles, people with disabilities, homosexuals, and communists. From the outset, Hitler propagated the idea that Jews were a biologically distinct and inferior species, reinforcing these beliefs through propaganda and laws such as the Nuremberg Race Laws, which legally defined Jewish identity.[4]

In doing so, Hitler went beyond merely giving a face and name to the enemy; he actively divided the German population into factions of supposed superiority and inferiority. Once Germans internalized the belief in their inherent superiority, it became far easier for Hitler to justify targeting and persecuting those he labeled as threats. Amid the chaos, Hitler successfully redirected public loathing toward a specific group—one he had meticulously portrayed as different and dangerous.

In the United States, the Red Scare of the mid-20th century provided another stark example. During this period, political leaders such as Senator Joseph McCarthy exploited fears of communism, accusing countless individuals—often without any evidence—of being communist sympathizers or spies. This tactic of demonizing an ideological "other" allowed McCarthy to gain influence, dominate headlines, and stifle dissent. The consequences were far-reaching: countless careers were ruined, lives were upended, and public trust in institutions was deeply eroded.[5]

As the late French theorist of mythology, René Girard observed “the target is not chosen because it is in any way responsible for society’s woes … The scapegoat is instead chosen because it is easy to victimize without fear of retaliation.”[6] In this way, monumental social issues can be pinned on select, blameless groups who are less understood by the majority due to their different customs and cultures. Politicians who effectively employ these techniques are often celebrated for exposing the supposed injustices that have wronged the public for so long. By doing so, demagogues make themselves out to be not just champions of the people, but their saviors—an illusion that history has shown can be as dangerous as it is seductive.