Through the calculated use of seemingly innocuous buzzwords or “dog whistles,” politicians can quietly stoke racial fears and anxieties that reside just beneath the surface of a target audience. They can achieve this without taking the political risk of openly appealing to racism, as the implied messages can be dismissed as coincidental or misunderstood, while still resonating powerfully with the intended group.

This type of calculated obscurity was not at play back in 1964, when Conservative Party members in the UK campaigned with the slogan, “If you want a n***** for a neighbour, vote Labour.”[1] Although the Labour Party won the election, the tactics were later described by the Prime Minister as “utterly squalid,” reflecting the changing times and a shift in public sentiment away from such overt forms of racism.

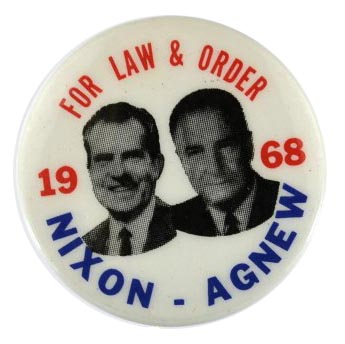

Using a similar strategy, in 1968, U.S. presidential candidate George Wallace ran on an openly pro-segregation platform. Despite his popularity in Southern states, he was defeated in a landslide by Richard Nixon. Nixon’s more nuanced calls for “law and order” effectively played into the same fears of white suburbanites about encroaching ethnic minority communities and court-ordered busing, while also being palatable to a wider majority of voters.[2] The term “law and order” subtly evoked racialized imagery of urban crime, enabling Nixon to mobilize his base without alienating moderate voters.

This strategic ambiguity continued with Ronald Reagan during his 1976 presidential campaign. In campaign speeches, Reagan repeatedly told variations of a story about a woman from Chicago’s South Side who allegedly defrauded the welfare system:

“She has 80 names, 30 addresses, 12 Social Security cards, and is collecting veterans’ benefits on four non-existent deceased husbands. She’s got Medicaid, getting food stamps, and is collecting welfare under each of her names. Her tax-free cash income is over $150,000.”

While he never explicitly mentioning race, Reagan’s vivid description played into racial stereotypes, as many listeners inferred that the woman he described was Black.

The media and political commentators later coined the term "welfare queen" to encapsulate this narrative.[3] By repeating this story, Reagan stoked resentment toward social safety nets among white voters, reinforcing racialized fears without overtly racial language.

Taking a similar approach, in a 1996 speech championing her husband’s crime legislation, Hillary Clinton painted a dehumanizing picture of marauding inner-city teens:[4]

“They are often the kinds of kids that are called superpredators – no conscience, no empathy. We can talk about why they ended up that way, but first, we have to bring them to heel."

While Clinton did not explicitly single out Black or Brown youth, it was widely inferred that she was doing so. This inference underscored how dog whistles can operate effectively within a broader discourse on crime and punishment, simultaneously reinforcing racialized fears while maintaining plausible deniability.

More recently, the controversy over Critical Race Theory (CRT) has turned into a modern dog whistle. CRT, an academic framework examining systemic racism, has been co-opted and redefined beyond its original academic meaning to stoke fears and anxieties about discussions of race, equity, and systemic discrimination. Opponents argue that CRT is “divisive” or teaches children to “hate their country,” while signaling support for resistance towards societal shifts toward inclusivity and diversity. This vagueness allows politicians to stoke anxieties about demographic change while deflecting accusations of overt racism.

Like CRT, “wokeness” also functions as a dog whistle by framing discussions of race, equity, and systemic discrimination as excessive or harmful. Originally a term from Black communities that called for awareness of systemic injustice, the term has been co-opted and weaponized to dismiss or denigrate equity efforts, diversity initiatives, or any discussion of systemic racism or gender inequality. This ambiguity allows the term to be applied to a wide range of issues, making it difficult to counter and allowing critics to delegitimize the voices of marginalized groups by framing their concerns as overreactions.

In this way the dog whistle carries on as a reliable instrument to gain votes from the further ends of the political spectrum, without alienating the wider majority of voters. It provides politicians with a stealthy way to signal allegiance and allows them to deliver racist messaging—all while granting them plausible deniability in the process.